O! brother moon, what do you eat?

“I eat eggs,” says the moon.

Where are the eggs?

“They’re on the table,” says the moon.

Where is the table?

“It was burned by the fire,” says the moon.

Where is the fire?

“It was extinguished by water.”

Where is the water?

“Drunk by the cow.”

Where is the cow?

“Vanished into the earth.”

This story, if you can call it a story, was told to me again and again, mostly by my grandmother and sometimes by my mother. There is no central character, no obvious conflict, no satisfying pay off at the end. Such were the stories told to me when I was young.

I now realize that stories are the spine, heart, lung, and breath of being human, even stories that are weird, pointless, logicless, and lacking a tidy moral. Maybe the logicless stories are even more important. Stories can be potent means for shaping the way we think. It is believed that in the ancient Kingdom of Tibet, one of the methods of leading the nation was through storytelling.

I can see the powerful imprint stories made on me as a child. Because of that moon story, I remember looking at the moon very intently and believing that the moon ate omelettes. I observed the whole sky and I could see all the different colors of the stars. Now when I look at the sky, the color of the stars seems to be forever gone. As with everything, impressions and perceptions fade and drift.

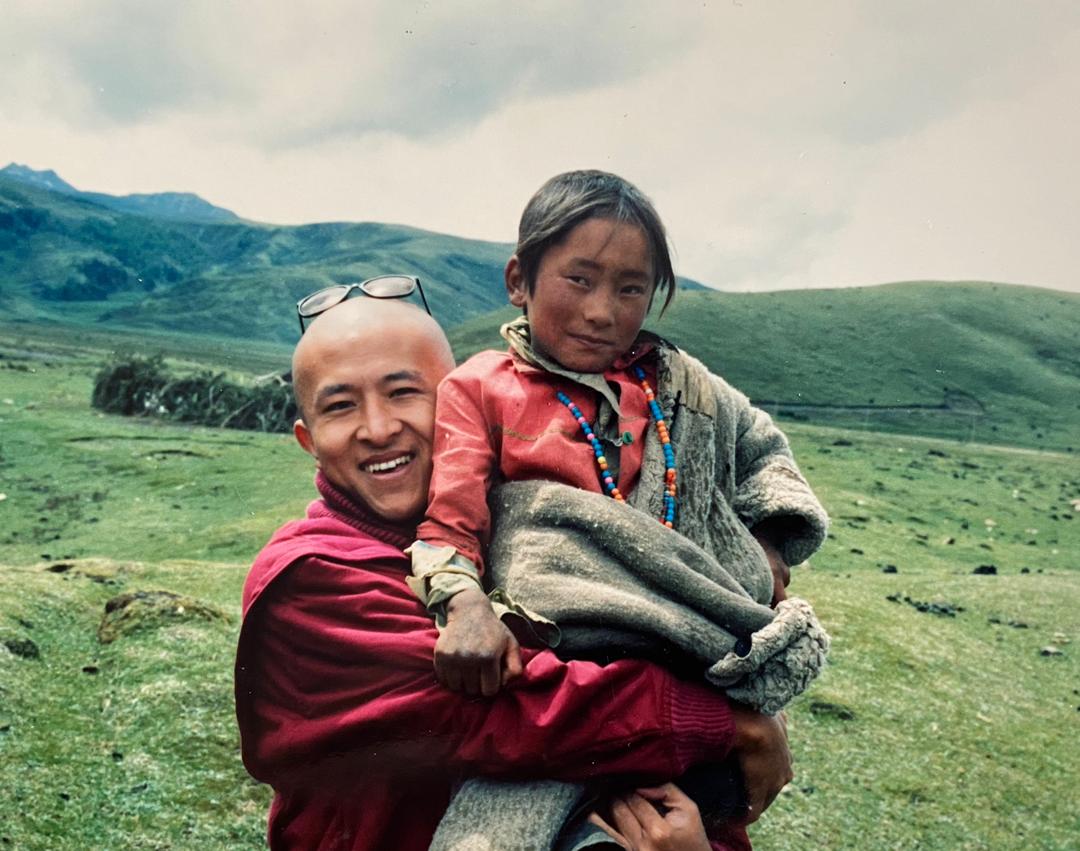

People say when you get old you became senile or more childlike. If that means that you begin to return to your childhood memories, then I think it’s true. It’s been more than 40 years since this story of the moon was told to me, and I had almost totally forgotten it, but suddenly last year, I had a glimmer of a memory of it and I wanted to hear the whole thing. I went to great lengths in search of the source. It took many months, speaking to many people, and finally I found some elders in my home village of Kurtoe in Bhutan who could remember the story, although they had several different versions.

Growing up in Bhutan and Sikkim, there were some very good storytellers and I would beg them to tell me tales. There is something profound in the language Bhutanese children use when asking for a story. They say, rungma te shigbi. Rungma, among other things, connotes a binding or a knot, and shigbi means “please undo”. So in other words, they are essentially asking for the opening of the package, the undoing of the bindings so that the story can be released. If the storytellers consented, all of us children would drop everything and wrap up cozy in blankets, even if it was daytime, and we would settle in to be mesmerized.

There was one story about a dog, an emanation of Tara, who led a boy to many different places, to experience different aspects of life. I am still trying to recollect this particular story. Then there was the popular story of the Four Harmonious Friends – an elephant, monkey, rabbit and bird – and how they were all good friends living in a forest. There was a big tree in the forest, bearing some really good fruit. But because the tree was very tall, individually they couldn’t reach the fruit. Long story short, they all stacked up on top of each other, monkey on top of the elephant, rabbit on top of the monkey, and the bird on top of the rabbit so that the bird could reach the fruit and hand it down for everyone to enjoy. In this story, it was the bird who came up with the idea and we were told that this bird was none other than the Buddha in his previous life. The moral of the story was that no matter the species or size, whether you have feathers or tusks, as long as you come together and work together, you will be able to reach the fruit, or whatever it is you want to achieve.

There was also the epic story of Gesar of Ling, whose running tale of talking swords and a horse with four eyes (two on the bottom) kept us fascinated for months at a time.

Since then, Cinderella, Harry Potter, Alice in Wonderland, have taken over. The days of pointless, dramaless, and conflictless stories seem to be over. I wish all children in the future could experience rungma te shigbi, the continuous undoing of the continuous knot.

There’s no punchline here because this is the story about no punchlines.

Recent Comments